Blockchain for empowering the

artistic culture: the case of Smart

by Silvia Semenzin

Co-authors: Silvia Díaz Molina, Elena Martínez Vicente, Maria Cruz Valiente, Jorge Saldivar

Data Range: 2018-21

Region: Spain

Methodologies

Social research

• Semi-structured Interviews

• Focus group

• Participant observation

• Documentary Analysis

Technology

• Ethereum

• Infura

• IPFS

• React

• Solidity

• web3

Design

• Lean Design

• Design Thinking

• Co-creation Workshops

• Prototype & Iteration

• User test

Smart Coop (an acronym for Société Mutuelle pour artistes) is a non-profit European organization that aims at ensuring administrative and legal coverage to freelance artist workers during periods of both activity and unemployment [1]. Smart is the largest cooperative in Europe, with more than 120,000 members in 8 different countries, and offers different services to creative workers in terms of training, legal assistance, microcredits, crowd-funding, insurance, webinars and meetings. The project was born in Belgium, but it expanded over time and nowadays has 7 other branches around Europe, i.e. Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Sweden and Spain.

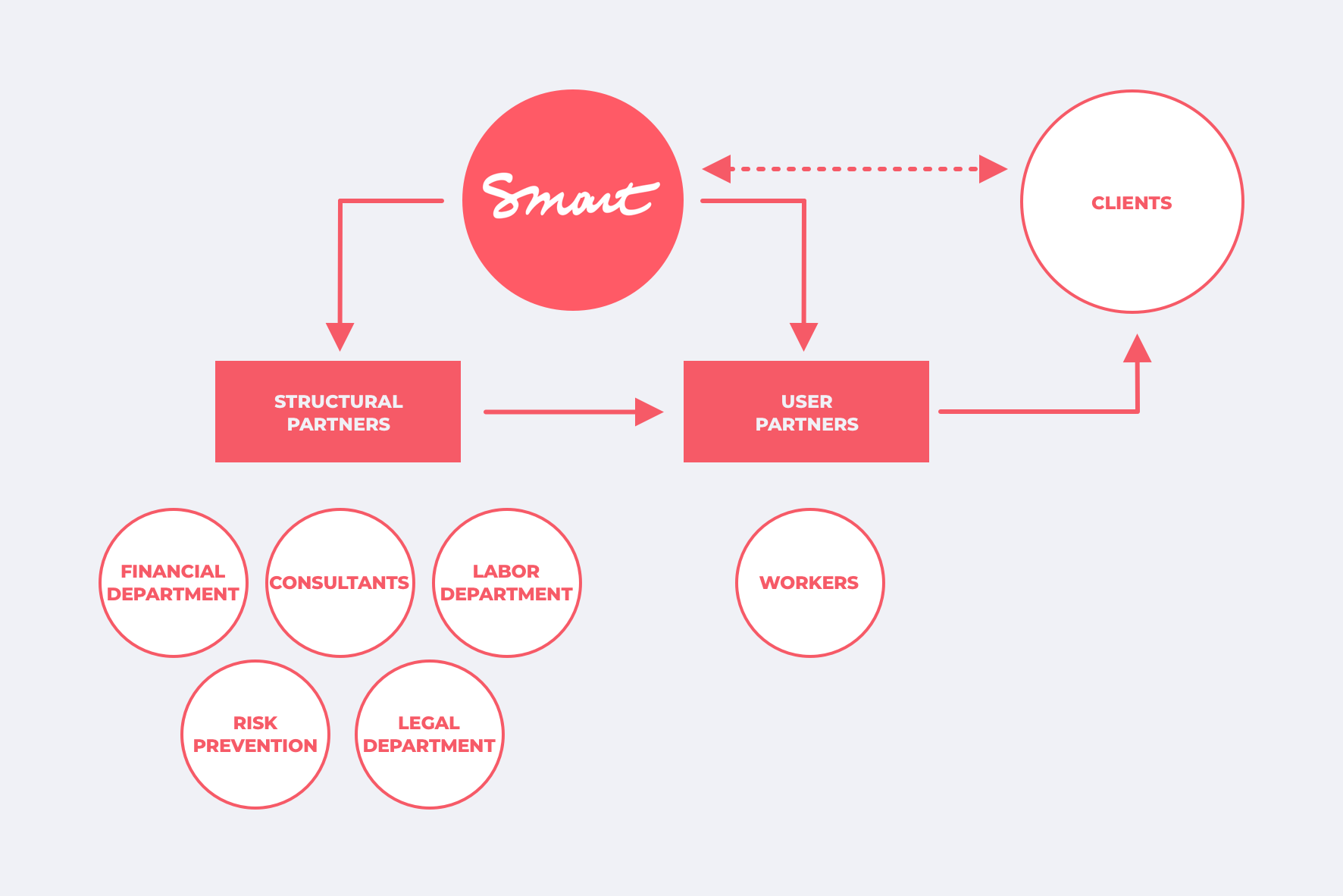

The Spanish section of Smart is known as SmartIB and has been active since 2013 [2]. In Spain, SmartIB was constituted as a non-profit cooperative driven by entrepreneurship, reminiscent of social enterprises. SmartIB presently has official delegations in Madrid, Barcelona and Seville, but it operates throughout the entire country. In the last 7 years, SmartIB has attracted more than 3,000 members, with 1,500 of them currently active. There are 7 assessors who are in charge of supporting and helping members navigate Smart bureaucracy and activities, as well as offering them legal and professional assistance (Figure 1).

Figure 1- SmartIB structure. Source: SmartIB

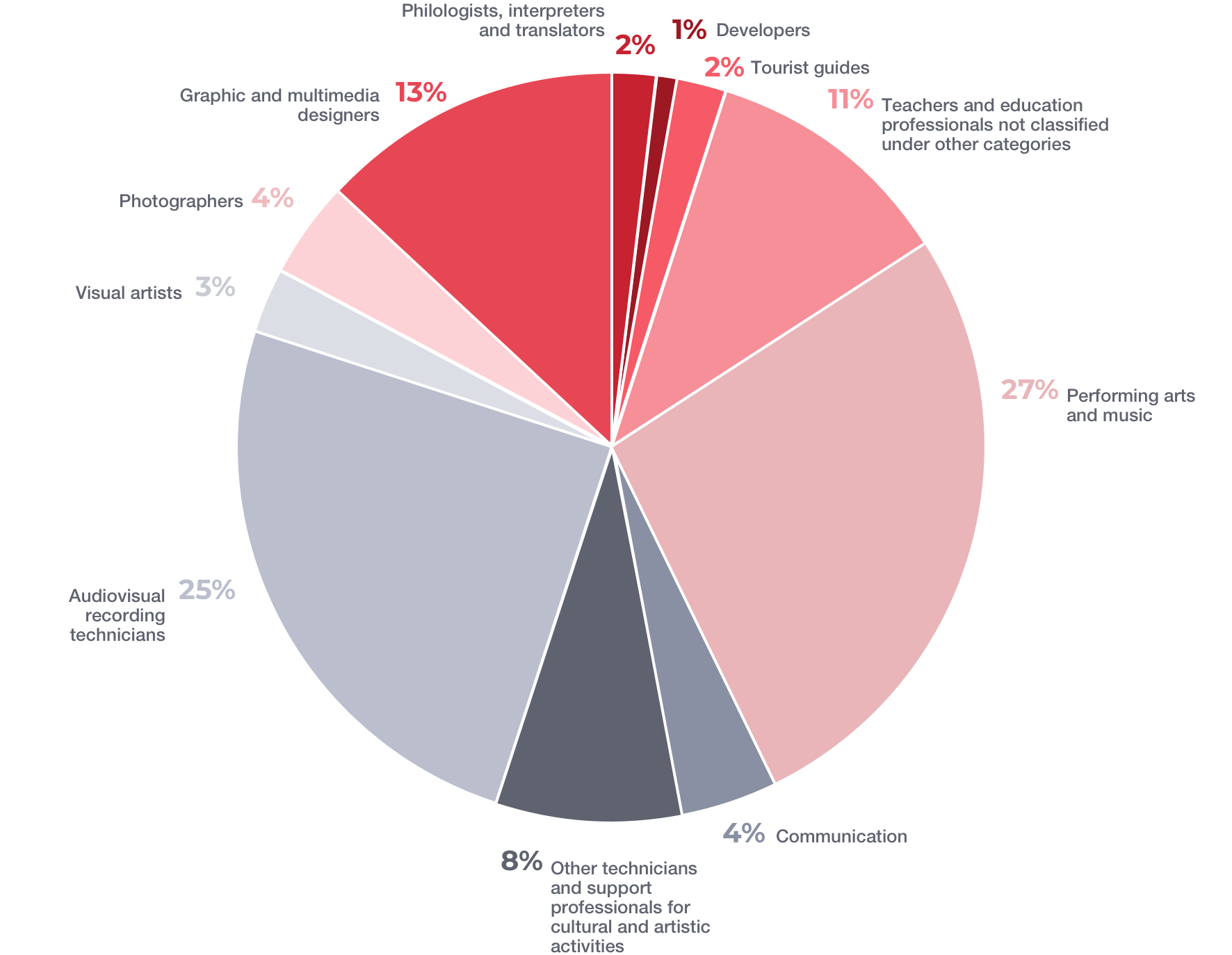

Smart brings together a wide variety of professionals within the category of “cultural workers”. Among these, we can find:

Figure 2. Smart categories of professionals

Selection of the case study

Smart was born with the aim of minimizing creative workers’ individual risks by sharing losses and benefits inside the cooperative. To do so, they essentially guarantee that artists will be paid by companies on time and act as an intermediary between them.

The work of the cooperative can be framed in terms of social economy, since every gain made by Smart is reinvested in maintaining the structure and services available to its members. However, Smart serves as a proper example of solidarity economy too [3], since it addresses the adverse effects of the dominant economic system emerging in times of social crisis and aims at fostering relationships of mutual support and solidarity. According to SmartIB, there are seven core values that characterize the management of the cooperative [4]:

- Open and voluntary membership

- Democratic administration

- Dconomic participation of members

- Autonomy and independence

- Education

- Training and information

- Cooperation among cooperatives

- Community engagement

Il Quarto Stato, by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo

Smart’s goal is to improve the working conditions of artists and creatives on a large scale. Since the cultural and artistic sector suffers serious precarity and uncertainty, the cooperative aims at providing cultural workers with a network of support and financial aid. In doing so, over the last several years Smart has indeed been able to assemble a community of otherwise unconnected peers [5]. In fact, Smart’s motto affirms that: “Intermittency is not a synonym of precarity”, recognizing that the cultural and artistic sector requires further attention and regulation from the public sphere. From their point of view, artists and creatives should be able to reach their professional potential without suffering more disadvantages as compared to other sectors. Moreover, societies should acquire a deeper understanding of the diversity of this work sector.

Our vision: “Distributed governance for social economy”

Cooperatives are the best-known example of social economy enterprises. Cooperative governance is based on three pillars: democratic control, shared ownership and member empowerment. They are the most “democratic by design” enterprises, however they prove to operate more slowly and are therefore less competitive than capital-based enterprises. As Mannan [6] suggests: “Turning to the coordination issues that occur upon the formation of worker cooperatives, collective action theory suggests that the heterogeneous preferences of equal worker-members make it difficult to arrive at decisions expeditiously”.

We believe that distributed technologies, and specifically Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), may enable cooperatives to have a more agile governance model.

A DAO is usually defined as an organization in which participation is mediated by an embedded set of rules, implemented in the form of smart contracts [7]. Parallels can be traced when compared with a legal organization in which legal documents define the rules of participation among members. Analogously, interactions between the members of a DAO are embedded in the code of smart contracts. These rules are automatically enforced by the underlying technology: the blockchain.

Saul Bass

In the case of cooperatives, it is claimed that the blockchain may be able to enhance new models of distribution of power and value and help social economy enterprises to have a more agile decision-making process. Our scope includes testing the extent to which certain assertions can be considered valid, since many scholars argue that “blockchain technology makes it possible to replace the model of top-down hierarchical organizations with a system of distributed, bottom-up cooperation” [8]. In this sense, we started our work with Smart by researching its communitarian needs, trying to come up with creative ideas of intervention and asking ourselves how the blockchain could be included in the process. More specifically, we aim to study the possibility that the blockchain could function as an empowering tool in the context of social economy, as it is able to construct digital peer-to-peer networks. Moreover, we are interested in its potential for “commoning the infrastructure” [9], referring to the idea of helping design infrastructures that favor the expansion, proliferation and networking of commons.

What are we experimenting with

As a research group, we are experimenting with blockchain technologies to help collaborative economy organizations work in a more decentralized way. Our hypothesis is that, by introducing the use of smart contracts and transparent ledgers, the blockchain can help these organizations to exchange information without having to rely on a central point of control. In this case study, we first needed to identify the best point of intervention to do so.

Photo by Efe Kurnaz on Unsplash

Stage One. Evaluation of points of intervention

The collaboration between P2P Models and Smart started in December 2018, when the P2P Models research group approached Dr. Rocío Nogales Muriel, the author of a PhD thesis that used SmartIb as its main case study [10].

To begin studying the needs of the community, P2P Models engaged in 14 formal, semi-structured interviews with Smart members. It also conducted informal conversations with four other members. All formal interviews were transcribed and analyzed qualitatively with the aim of highlighting challenges and difficulties that the community might face.

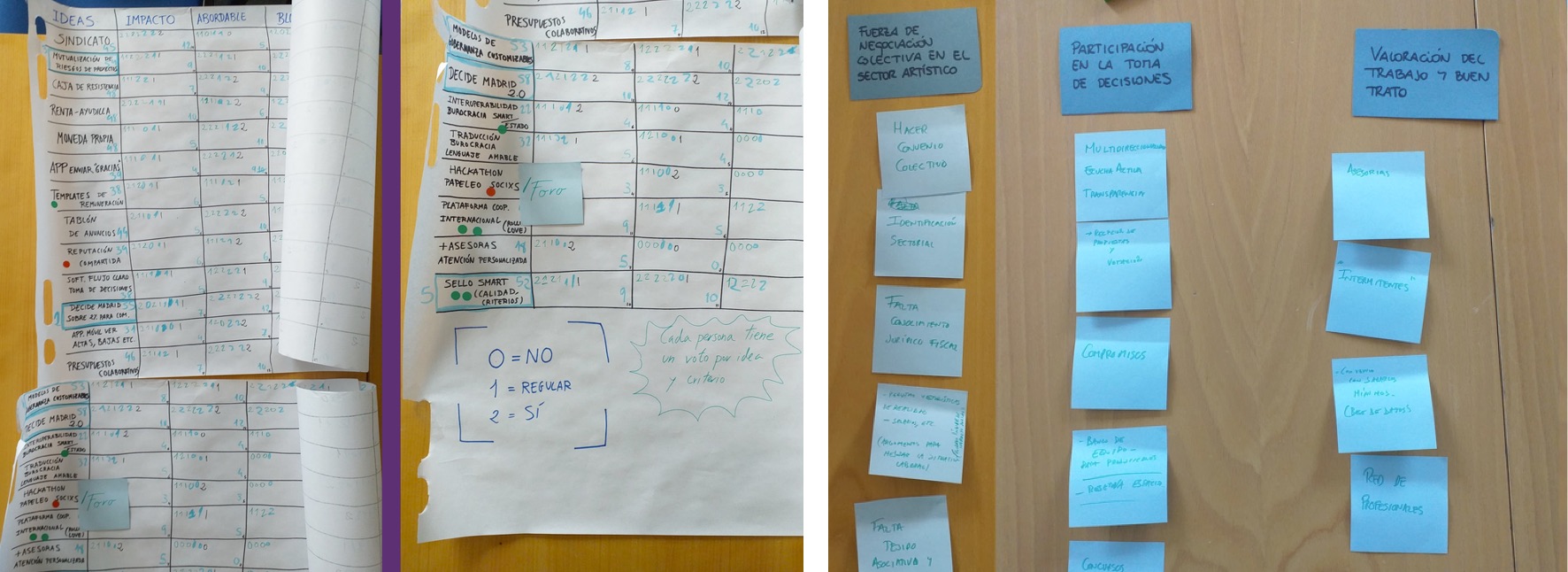

Moreover, the research group also relied on participant observation strategies in Smart Madrid spaces in order to get a clearer sense of the cooperative’s environment and general practices. By using design thinking methodologies and by filtering through the needs expressed in the interviews, two workshops were organized with four cooperative members to validate our hypotheses. The main goal of these workshops was both to confirm the initial results emerging from the interviews, as well as to collect impressions, ideas and suggestions for improving how Smart works.

Workshop with SmartIb

Out of our first few dialogues with the community members and participant observation, a number of needs emerged, mainly concerning:

- The internal and external transparency of Smart operations

- The simplification of a complex process of bureaucracy

- The construction of a more solid network of professionals

- The encouragement of a lobbying process headed by Smart to improve working conditions in the cultural sector.

Workshop with SmartIb

These results were again validated with the community by means of a survey sent to Smart members to evaluate our initial analysis.

Once this first stage was completed, P2P Models elaborated different ideas for intervening in the community using the blockchain. We discarded the use of programs that were too complex and resource-demanding (such as the creation of a Smart cryptocurrency for value distribution), and instead implemented an initial blockchain-based prototype that tackled Smart’s information systems first. After analyzing the points of intervention, we became interested in developing a service that would allow Smart to organize and speed up their internal information management by using the open, transparent ledger.

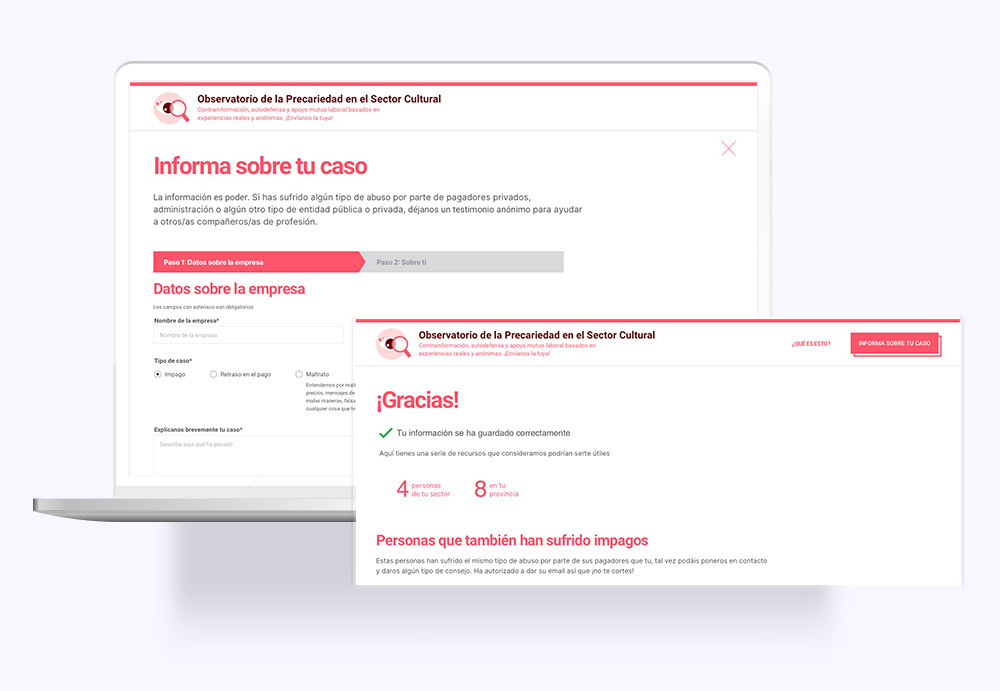

Stage 2. First prototype and testing

The first prototype arose from a compelling necessity to intervene in the flow of Smart bureaucracy and help the cooperative to systematize their work. On the one hand, this translated into working on external transparency and clarity in the onboarding process for new members. On the other hand, we also considered the workload that the manual onboarding process requires and tried to automate it.

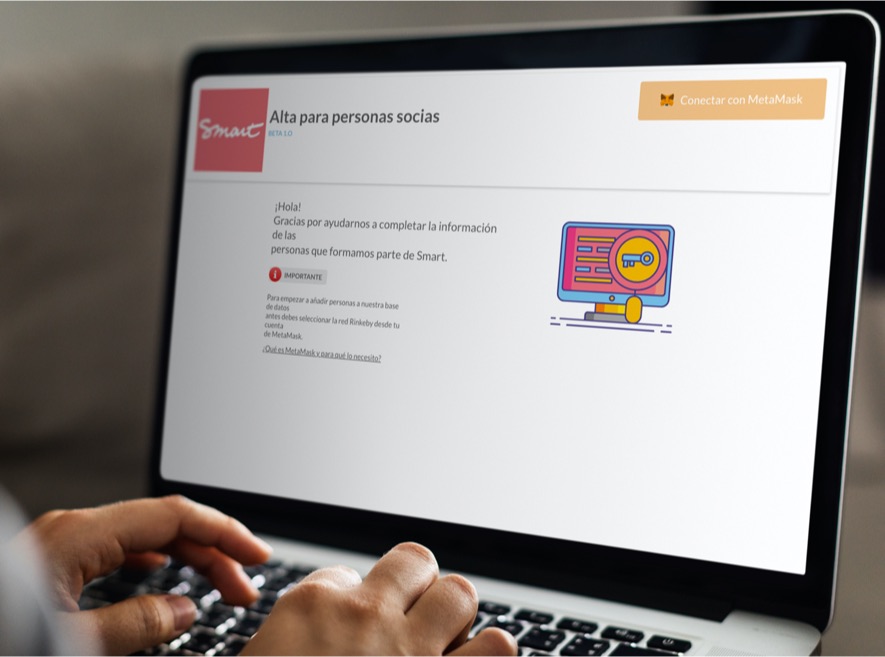

The prototype elaborated by P2P Models is called “Open.Smart”. Basically, the prototype is designed as a transparent database which serves to collect and order Smart member data. These data are supplemented by other records and documents required for subscription and are saved and encrypted in the blockchain. Open.Smart is an external app that relies on a digital wallet called Metamask that makes it possible to interact with the Smart platform (Figure 3 illustrates the beta version of Open.Smart)

Figure 3. Open.Smart Beta version

Once the Beta version was ready, we started testing our prototype with the assessors and saw what challenges or difficulties may arise.

In general, although the assessors showed enthusiasm for Open.Smart and expressed motivation in engaging with technology that helps them in systematizing their manual work, we have identified major issues with installing Metamask and understanding blockchain technology. This led us to question the relevance of the prototype for the Smart community and consider the possibility of focusing on implementing a more user-friendly and community-oriented prototype. In terms of research for P2P Models, in fact, it remains relevant that the current prototype does not directly tackle the idea of distributed governance or value, though it still focuses on the importance of enhancing transparency inside cooperatives through decentralized technologies. For this reason, the implementation of the second prototype aims at further investigating the possibility of using the blockchain for enhancing horizontal and tamper-resistant networks, in line with our initial hypothesis.

Stage 3. Workshops and survey

Currently, the Spanish cultural scene has been severely affected by cuts in the public sector. Although it generates 3.7% of the total GDP, the cultural and artistic sector in fact only receives about 0.43% of Spanish Public Administration funding. In this context, cultural workers are struggling more and more to survive the crisis [12].

In the previous workshops, SmartIB’s members described a need to create more networks among cultural workers and find strategies to make their working conditions public. Therefore, in the third stage of our experimental research with Smart, we decided to explore this need further and test the possibility of using blockchain transparency to expose the financial conditions of cultural workers and make sense of the current difficulties that affect this sector.

To do so, we have conducted a series of workshops with SmartIB members, asking them to discuss how precarity affects their jobs and lives and to what extent they consider technology useful to make this issue more visible. Among the participants 50% were male and 50% women, working in different areas of the cultural professions, for example, performing and audiovisual arts, education, linguistic translation and journalism and graphic arts. Whilst in the first workshops we welcomed participants of all ages, in the third and last we decided to focus on young people (this is due to our need to retrieve strong opinions on social media and technology).

In the three workshops that we conducted in 2021, we asked members to share their experiences of non-payments or delays in payments, as well as if they ever experienced situations of unfair treatment with clients. Furthermore, we encouraged them to imagine solutions that could be carried out through technology, following the principles of data activism [13].

The results of the workshops showed that non-payments, delays and mistreatment are serious issues for cultural workers. Participants generally showed a positive attitude towards technological means, which they considered both useful for their jobs and for denouncing unfair conditions (e.g. through social media call-outs).

To validate our initial results, we also sent a survey to active Smart members, which had 65 replies. Overall, the survey confirms the workshops’ results:

- For 43%, delays are frequent and 92% say they think it is interesting that information about delays is shared among Smart members.

- 50% were not paid at least once.

- 98% find the idea of having a collective reporting tool appealing.

- 81% say they would like to know if the company that is going to hire them has a history of non-payment or delays.

- Almost 60% say they have medium-high skills with technology, and 3/4 consider that technology helps them in their profession.

The main goal of our workshops and survey was to explore the advantages of blockchain for the construction of a decentralized, immutable, and uncensorable system that allows users to denounce companies and make the precariousness of the Spanish art sector visible. Since some participants highlighted the ephemeral nature of social media indignation, we considered that the construction of a permanent platform of public denouncements could better serve the data activist purpose.

Acabo de cobrar una factura de 2018 de un museo. #60Días

— Rubén H. Bermúdez (@RubenHBermudez) May 6, 2021

#truestory

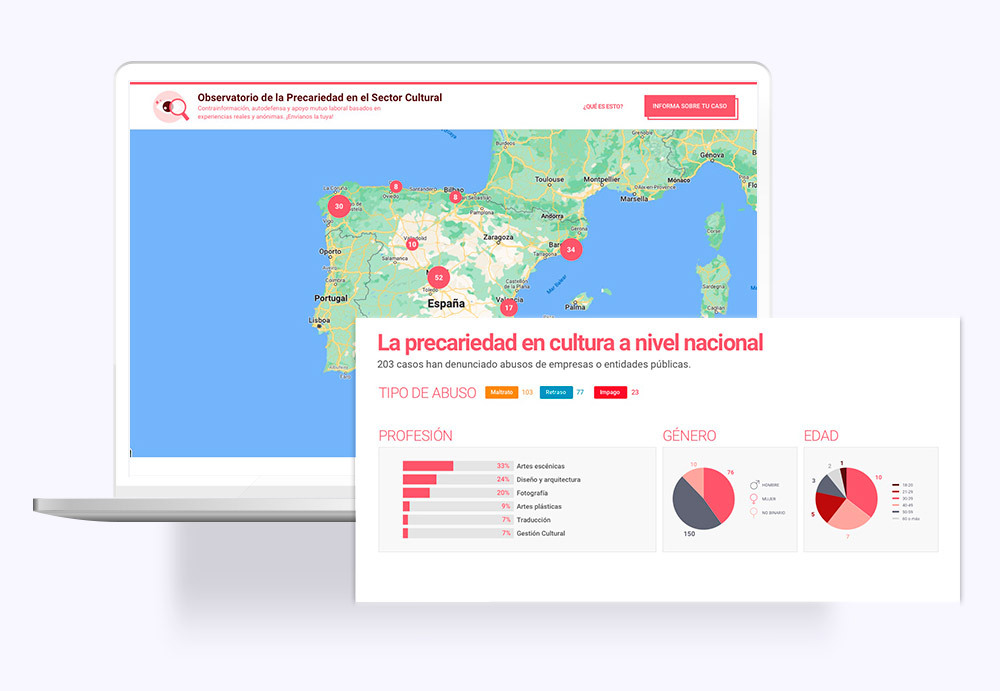

Stage 4. Observatory of Spanish Artistic Precarity

Following this idea, we arrived at the design of our second prototype. We called it ‘Observatory of Spanish Artistic Precarity’. The Observatory is thought of as a dynamic platform that visualizes metric data regarding current worker conditions and provides more visibility to the problem of precarity for cultural workers. At the same time, it allows users to create networks with each other and reach out to help entities after posting their public denouncement. Thanks to blockchain technology, the platform will be transparent and harder to censor (contrary to other projects based on mainstream platforms, e.g.@TrabajosRuineros). By relying on a set of quantitative data provided by users, we should also be able to visualize and address salary gaps depending on gender, location and type of (artistic) profession, which can help further analysis and policy-making around precarity. Moreover, this may serve as a seal of quality for improving Smart’s reputation, both as part of the collaborative economy and as a way to enhance lobbying against precarity.

The prototype has three main goals:

- Monitorization: provide data to organizations and collectives in order to develop strategies for solving this issue through social means.

- Visibilization: raise awareness of job insecurity in Spain to the public.

- Collectivization: ease the process of contacting organizations, collectives and individuals with similar issues with the intention of increasing social participation outside the digital sphere.

With the prototype that is now being implemented, we aim at focusing on the reputation and reliability of different companies. In this way, we should be able to curb the negative effects on the reputation of cultural workers [14] while showing the salaries and conditions offered by different companies.

Ongoing research and next steps

In the next and final phase of our research, we plan to implement a beta version of the Observatory and run a number of user tests to measure the platform impact. User tests are research methods developed by the Human Centered Design (HCD), which aims at evaluating a digital product. Through this evaluation, we will seek to justify the decisions taken during the research process within the community, and check that the prototype meets the needs and expectations that have arisen during the workshops with Smart.

User tests will be conducted by asking participants to highlight both the advantages and limitations of the platform, in order to acknowledge the opportunities offered by the prototype, as well as the possible constraints that may discourage data activism in the context of precarity. After carrying out these tests, the prototype will be optimized with the results and left in a GitHub repository so that any community with similar problems can use it.

User tests will be conducted by asking participants to highlight both the advantages and limitations of the platform, in order to acknowledge the opportunities offered by the prototype, as well as the possible constraints that may discourage data activism in the context of precarity. After carrying out these tests, the prototype will be optimized with the results and left in a GitHub repository so that any community with similar problems can use it.

More information

Related info

References

[1] SmartCoop [Cited 25 Feb 2021] Available: https://smart-ib.coop/

[2] SmartIB [Cited 25 Feb 2021] Available: https://www.smart-ib.coop/

[3] Miller, E. Solidarity Economy: Key Concepts and Issues. In: E. Kawano, T. Masterson, and J. Teller-Ellsberg, editors, Solidarity Economy I: Building Alternatives for People and Planet, Amherst, MA: Center for Popular Economics; 2010. p. 25-41.

[4] Smart Ibérica. Una apuesta colectiva para la articulación del sector profesional de la cultura en España. Internal report. December 2020.

[5] Muriel, R. N. La empresa social en Europa y España: evolución, relevancia y desafíos. Tercer Sector, 2017, p. 117-140.

[6] Mannan, M. (2018). Fostering Worker Cooperatives with Blockchain Technology: Lessons from the Colony Project. 2018 [cited 18 Feb 2021]. doi: 10.5553/ELR.000113.

[7] Valiente Blázquez, M.C., Hassan, S., Pavón Mestras, J. Evaluating the Software Frameworks for Developing Decentralized Autonomous Organizations. 2020. Available: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/62240/7/DAOs_SW_Frameworks_Evaluation.pdf

[8] De Filippi, P. What blockchain means for the sharing economy. Harvard Business Review. 2017, pp. 4 [cited 18 Feb 2021]. Available: https://bitcryptonews.ru/img/documets/What_Blockchain_Means_for_the_Sharing_Economy.pdf

[9] Vieira, M. S. Commoning infrastructures, infrastructural commoning. In: Slides and transcript of the Infrastructure keynote at the Economics and the Common (s) Conference. Berlin. May 2013 [Cited 19 Feb 2021] Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2620849

[10] Muriel, R. N. Social transformation and social innovation in the field of culture: The case of the SMart model and its adaptation across Europe. PhD Thesis, Dep. of Sociology, University of Barcelona. 2017. [Cited 18 Feb 2021]. Available: http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/117171/1/RNM_PhD_THESIS.pdf

[11] Riaño, P. El empleo cultural: más formado pero más precario. El País. February 8, 2019. Available:

[12] Cuenta Satélite de la Cultura en España. Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. November 26, 2020. Available: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano/estadisticas/cultura/mc/culturabase/cuenta-satelite/resultados-cuenta-satelite.html

[13] Milan, Stefania, Data Activism as the New Frontier of Media Activism (January 31, 2016). in “Media Activism in the Digital Age”, edited by Goubin Yang and Viktor Pickard, Routledge (2017), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2882030

[14] Gandini, A. The reputation economy: Understanding knowledge work in digital society. Springer; 2016.