Who are the owners of collaborative economy?

P2P Models is a project which aims to support the existence and development of decentralized, democratic and collaborative economic communities that distribute value among their members. These three characteristics are fundamental to foster a cooperative economy platform based on the commons.

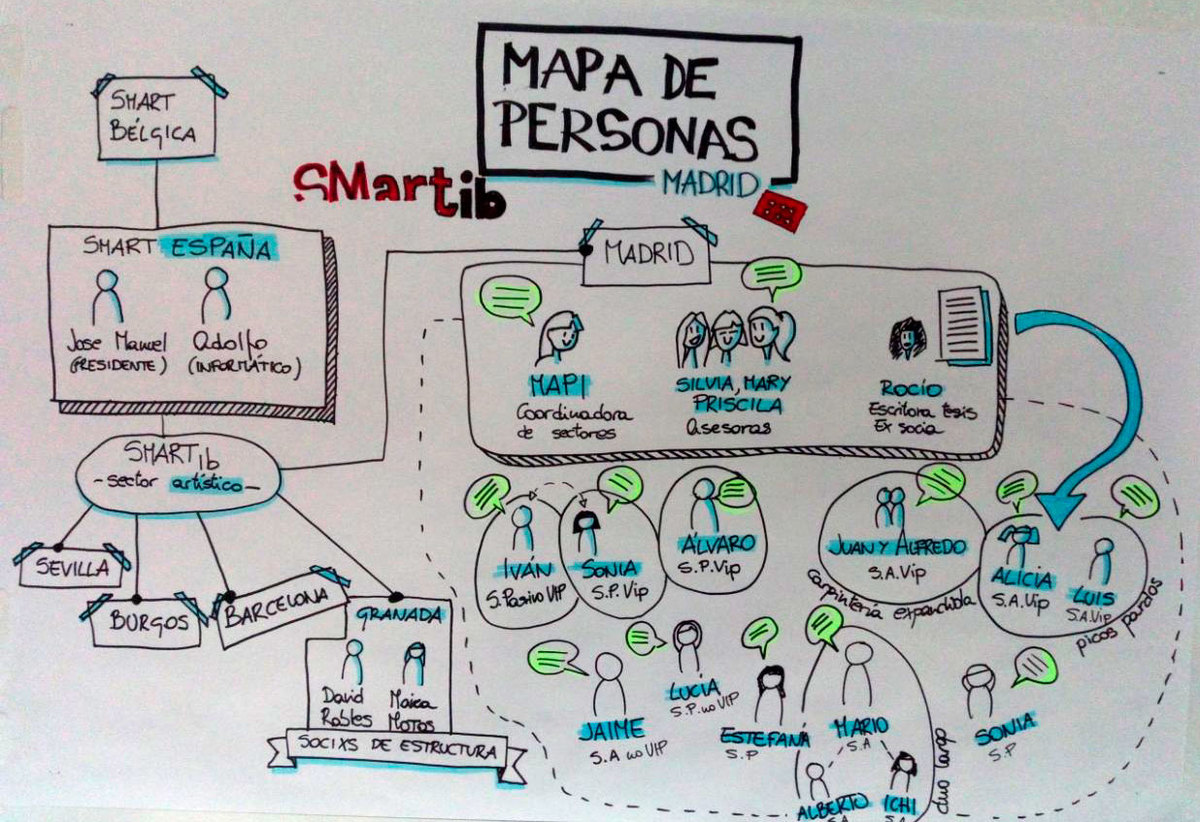

We work with different communities such as SmartIB and Amara as case studies, to test the different tools to be implemented depending on the needs identified. We believe in common decision making and analysis from within. This is why our approach is one of participatory research where communities are agents of decision making processes and take an active role in the design of the results. In order to do this, at P2P Models we are guided by six principles for our study processes.

Our criteria, our manifesto

In the beginning we decided to define how to proceed in the research, taking into account the communities. In our project proposal, the research approach was deductive: we would spend the first few months reviewing the literature, and after that, engage with the case study communities. In applying this logic, we realized that the area of study was vast: on the one hand, the field of the Collaborative economy, which encompasses a variety of initiatives with differing characteristics and on the other hand, the blockchain technology, a newborn technology whose potential has yet to be fully explored. These challenges pushed us to change the approach from deductive to inductive. We would throw ourselves into the field first and the results we found would guide the rest.

Once this decision was taken, we searched for communities that could be case studies which fulfilled certain criteria: complexity, size, age, degree of decentralization, decision-making structure and their value distribution model. Finally, we chose Amara and Smart as the first cases.

Once these were chosen, there were still many questions to be answered: Would our proposal fit their priorities and timings? Was the level of decentralization in decision making sufficient? What were their real goals? Most of our doubts arose from the fear of “promoting” a model that did not fit with the project’s principles. To avoid this, we first had to make the values that we want to define our research explicit.

Who are the owners of collaborative economy?

Who are the owners of collaborative economy?

Values that define our research

As a team, we assume the position of Donna Haraway regarding objectivity in research.

“We (feminist theorists) unmasked the doctrines of objectivity because they threatened our budding sense of collective historical subjectivity and agency and our ’embodied’ accounts of the truth”. This is why we stand for “foreground specific positioning, multiple mediation, partial perspective, and therefore a possible allegory for feminist scientific and political knowledge”. We think that embodying the knowledge, embracing and accepting our partial perspective, is exactly what makes critical science.

We know that we are not objective, we know the influence left by the ideas and values of the people who carry out the research. Our objective is to carry out critical science, including all possible perspectives and questioning our own “starting point”. What do we want from this research? It was this process that allowed us to identify the need to make the values that we wanted to define the project explicit. These values are as follows:

Inclusiveness: Technological projects, because of their characteristics, sometimes reach very few people. We assume the challenge of making technology accessible for as many people as possible. We want to carry out an inclusive project, communicating in a clear and simple way, collaborating with people of diverse backgrounds and profiles. We also want this to be reflected in the tools we develop: they must be easy to use, accessible and considered for all people, regardless of race, sex or social class.

“

Our objective is to carry out critical science, including all possible perspectives and questioning our own “starting point”

Horizontality: To achieve horizontality within the project, we must review the situation of the team members from the most visible things, such as salary, to the most invisible, such as trends in the most informal decision-making. This is not an easy task, although we have had workshops on the subject – a workshop with Loomio’s team, an expert organisation in horizontal decision making – it remains a challenge for us. We also want to have as horizontal a relationship as possible with the communities studied, to overcome the classic unequal position between the researcher and those being researched. The solution is once again to make everything as explicit as possible, to address the communities by making what we need from our side clear, and at the same time, to create an atmosphere of trust so that they too can make their needs clear.

Feminism: Mainstreaming the gender perspective throughout the project is crucial for us. In our team we have an expert anthropologist in gender studies. Her role is to make this perspective effective both within the project and in the design processes with the communities. Since our project deals with collaborative economics, we have considered the field from the perspective of feminist economy. On the other hand, the biggest challenge for us is still facing up to power relations within our team. As a general practice, we assume that we should always apply the gender perspective, bearing in mind that each of our practices, as individuals and researchers, would have a gender impact.

Commons-driven: Elinor Ostrom’s work on the governance of the commons inspired the project from its start. We question the famous “tragedy of the commons“, and we believe that communal practices can be sustainable over time. Our interest in the subject led us to write one of our founding working papers “When Ostrom meets Blockchain: Exploring the potentials of blockchain for commons governance”, in which we relate the Ostrom principles with some properties of the Blockchain technology. Relating to technology, we believe free software, and of course all the tools created in the project, will be under this license.

The commons has also been a criterion when choosing our case studies. In the case of Smart, for example, we are interested in their service of mutualization of risks, in the case of Amara, their public subtitling service.

Diverse: Our team is made up of professionals from different disciplines, backgrounds and gender. When it comes to working with communities, we interview people with very different profiles and life experiences. We try to collaborate above all with people who are not BBVAh -white, bourgeois, male, adult, without disabilities, heterosexual (capitals in Spanish)- a concept used by Amaia Pérez-Orozco. We consider this a principle of social justice.

AUTHOR