After the Initial Public Offering Uber had in May, all the expectations around its value evaporated. Despite this, the figures of the investments in the company are still astronomical. In whose hands are the companies of the called collaborative economy?

In less than a decade, the most representative companies of the collaborative economy, such as Uber, Airbnb or Lyft, have reached stratospheric figures in investments and market value. In addition to these figures, the social conflicts they have aroused are striking.

In this scenario we find positions for and against collaborative economy. The former, represented by the business organisations that bring together the main collaborative economy companies, defend it as a disruption in obsolete markets in need of renewal. Schumpeter, the Austrian economist, defined as creative destruction the process of social transformation that accompanies innovation in order to introduce a new production function. The latter criticise it for being one of the worst examples of value extraction – work and capital – that is leaving a trail of damaged workers behind.

A Glovo delivery in Madrid Ekaitz Cancela for El Salto Diario

What do they say collaborative

economy is

According to Sharing España, the organization that represents the conglomerate of companies that are grouped under this label, and Adigital -the Spanish Association of Digital Economy-, there are three fundamental elements to define the collaborative economy: the existence of a digital platform, relationships between equals and the intermediation of supply and demand to take advantage of resources efficiently. We will analyse whether or not the collaborative economy meets the criteria established by the organisations that represent it.

Digital platforms, indeed, play a very important role. Mayo Fuster Morell, one of our advisors and a researcher in collaborative economy, social movements and digital communities at Harvard University and the MIT Center for Civic Media, says that “collaborative economy is a type of platform economy with collaborative characteristics. No one doubts the fundamental role that technology has played in the launch of this new way of relating socially and economically”. However, when we speak of “relationships between equals and underutilized resources” as fundamental characteristics, critical sectors raise their voices.

Our principal investigator, Samer Hassan, proposes three properties of platform economy: central hubs of information collect massive amounts of user data, and are mostly controlled by major industry players, its communities have no influence on the decision-making of the platforms and, finally, there has been a significant concentration of benefits in a few hands that do not redistribute revenues proportionally among people who share their resources.

In fact, when Sharing España talks about relationships between equals, it refers to a very small part of the cake, which are the users who exchange resources. However, behind the technology, there are large private companies. It is for this reason that Fuster warns that “the great challenge of the collaborative economy is that it can bring us much more savage capitalism and a sharpening of its extractive practices”.

“

The great challenge of the collaborative economy is that it can bring us much more savage capitalism and a sharpening of its extractive practices.

Mayo Fuster Morell

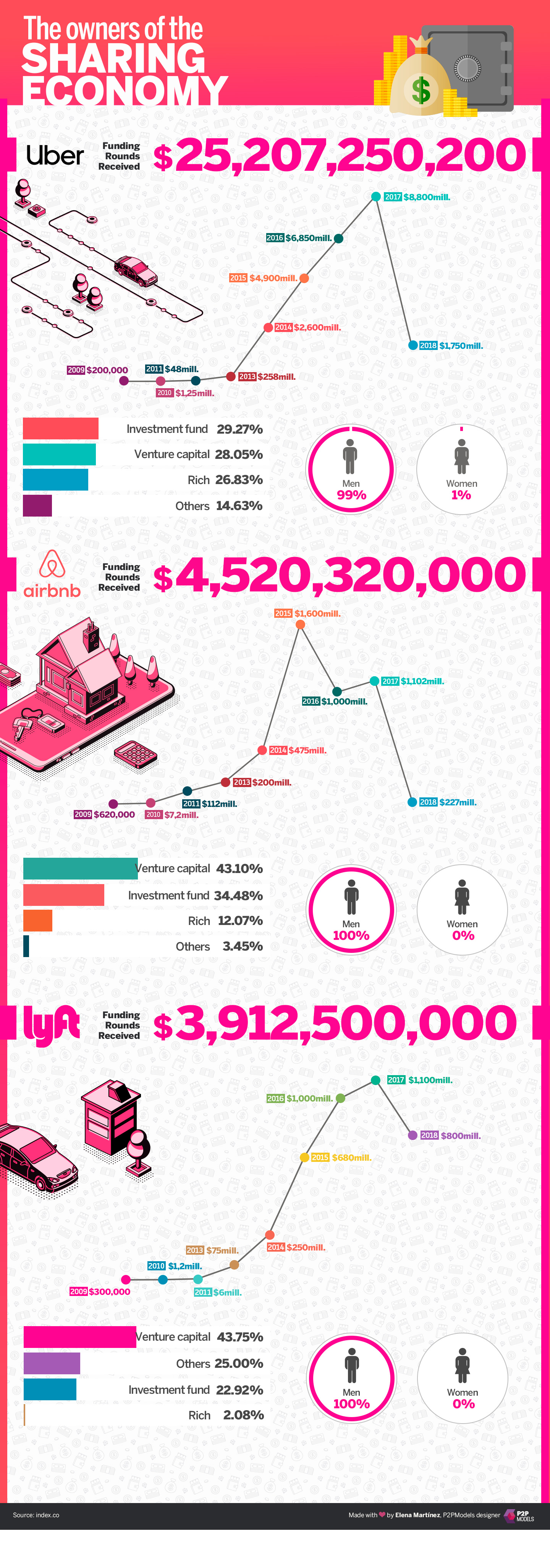

If we investigate the hands behind the main companies of the so-called collaborative economy, the concentration of capital becomes evident. Let us look at the examples of the largest:

Perhaps what these data show most is that the collaborative economy is a pure and hard financial economy. There is little collaboration and distribution of resources among equals.

According to author Nick Srnicek in his book Platform Capitalism, the financial and growth model of the collaborative economy is very similar to the dot-com bubble of the 1990s: “While many of these businesses lacked a revenue source and, even more, lacked any profits, the hope was that through rapid growth they would be able to grab market share and eventually dominate what was assumed to be a major new industry . […] It was an era driven by financial speculation, which was in turn fostered by large amounts of venture capital”.

Behind the three largest collaborative economy firms -Uber, Airbnb and Lyft- there are indeed a very high percentage of venture capital funds -companies that invest in high-risk, very disruptive businesses, and that seek immediate enrichment by also assuming possible losses-, investment funds, sovereign wealth funds and many wealthy men. This is not surprising.

The big three: Uber, Airbnb

and Lyft

The mobility giant Uber, located in San Francisco, present in 600 cities around the world, began its journey with a seed capital of 200,000 dollars, back in 2009. Over the years it has received investments worth $25 billion and has a market value of more than $120 billion. Despite these exorbitant figures, the company has only made losses. The latest data presented by the company in its internal reports showed losses of 1,100 million dollars. It is only during the last year that it made profits due to atypical circumstances – divestments in China, for example. For now, it seems to be only maintained due to the billionaire injections of money it receives from venture capital companies like Founder Colletive and Crunch Fund, banks like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley or Citigroup, technology giants like Google or Baidu, or big investors like Jeff Bezos -the founder and CEO of Amazon-, Troy Carter -of Spotify- or Scott Banister -of Paypal-. There are also public investment funds such as Saudi Arabia, which invested through its venture capital SBT more than 3,500 million dollars, or Qatar, which, through its Qatar Investment Authority, invested more than 1,200 million. On March 26, Uber bought Careem for 3.1 billion dollars, its analogue in Dubai, in an attempt to take over the service in the Middle East market.

In the case of Airbnb, also based in San Francisco, the pattern is the same. The company offers 5 million rooms in 81,000 cities around the world. It started with a seed capital of $20,000 and its market value is around $31 billion today. It has received funding worth 4.5 billion since its founding in 2009. Some of its investors are the same as Uber’s, although we also find new names, such as Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase or American Express, all of them giants of global finance. The Chinese government invested $100 billion in 2017.

Lyft was also born in San Francisco and has a similar business model to Uber. It was founded in 2012, with a seed capital of $300,000 and has currently received investments of nearly $6 billion from private investors such as Jaguar, Land Rover, various investment funds or Canada’s public pension investment fund. Its Initial Public Offering -IPO- took place on March 28 and has reached investments worth 2.2 billion dollars. Its current market value is 23 billion.

“

Of all the investments received by the three companies, only one woman’s name appears as an individual investor.

Of all the investments received by the three companies, only one woman’s name appears as an individual investor, Cyan Banister, an investor in Uber. The rest of the millionaires are men.

“Efficient use of resources”

We cannot ignore, as Samer Hassan states, the accumulation of capital, data and market share that is being carried forward by the platform economy and wrongy called collaborative economy.

Silvia Díaz-Molina is a researcher at our project specialized in the platform economy and its alternatives with an anthropologic and feminist focus. Silvia states that “it is difficult for the collaborative economy to achieve a change of model when it is immersed in the market economy. It plays its own rules and language and ends up reproducing the constitutive inequality of the neoliberal-capitalist system. Airbnb’s approach fits in perfectly with the dislocated and refined financial logic behind the expulsions that take place in global cities”.

What they told us that was going to be a new kind way of sharing resources is, today, another way of extracting value from the work of many people, with the aggravating factor of practically no contribution to the public system. “There are many derived effects. This type of capitalist extractionist platform has economic models of tax evasion and does not contribute wherever it operates. We think that Uber put at risk labor rights, but that’s not all, this economic model questions the welfare state as a whole,” warns Fuster.

It is necessary to carry out actions that propose alternatives to the platform model through collective ownership, democratic governance models, ownership of infrastructures and servers and exchanges, this time between equals. Fuster is still hopeful: “We can open up a horizon of economic democratisation that we did not have until now. The collaborative economy can point to the scalability of the social and solidarity economy, of cooperativism,” she says. According to the expert, the strength lies in the organization of cities to fight together against large corporations. The collaborative economy “puts on the board the role of cities because these companies are concentrated in them, but in our case the regulatory powers of the platforms are not in the cities, but in the European Union. It is necessary to revise a system of multigovernment to give more weight to the cities”. Likewise, she hopes for a platformization of local administrations “in the collaborative sense. They could adopt collaborative dynamics within the institutions supported by digital platforms, for example, in the case of Decidim, which is a digital platform used to decide policies in Barcelona city and it is a good case of how the platform economy can provide resources to improve public innovation and democratize institutions”.

Nick Srnicek does not see that there is such a clear cooperative alternative to the model. He proposes “investing the state’s vast resources into the technology necessary to support these platforms and offering them as public utilities. Maybe we should to collectivize the platforms”.

AUTHOR